Last month, Lucy, Alex and I travelled from London to the Jura Mountains in Eastern

France to visit Fort Saint Antoine, the famous ageing caves of Marcel Petite, one of

the most respected names in Comté cheese. It wasn’t just a tasting trip; I wanted to

see first-hand how the cheese is aged, and better understand some of the growing

concerns around Comté production.

As a cheesemonger, I’ve sold Comté for over half a decade. But not all Comté is

created equal and lately, that’s become a real point of tension within the industry.

Inside Fort Saint Antoine

Inside Fort Saint Antoine

Marcel Petite’s maturing caves are housed inside an old military fort built in the 19th

century, perched high in the Jura near the Swiss border. It was built to protect the

border with Switzerland in the Franco-Prussian war, and took approximately 600

masons, 600 stonecutters, and 3,200 soldiers to construct the fortress. 50 years ago,

Marcel Petite acquired the abandoned military fort because he saw the structure’s

potential for maturing cheese. Traditionally up to this point cheese was kept in

warmer environments that matured the cheese in a completely different way. Comté

used to have holes in it for that reason.

The cold, damp stone tunnels are now home to around 100,000 wheels of Comté.

Each resting quietly on spruce shelves for months, sometimes years, as they

develop depth and complexity. This isn’t cheese rushed to market. It’s aged slowly,

naturally, and carefully. Every single wheel is regularly tapped and turned by hand,

and then taste tested. As far as I am aware Marcel Petite is the only affineur to do

this. This means they can grade every wheel. But there are other factors that decide

the grade, appearance, rind quality, internal appearance and texture. The best

quality receive a green label with the iconic Marcel Petite green bell. The tier below

receive a brown label. Anything that is deemed not good enough is not allowed to be

sold as Comté. The environment inside of the fort is stable and low-energy, so no

refrigeration needed.

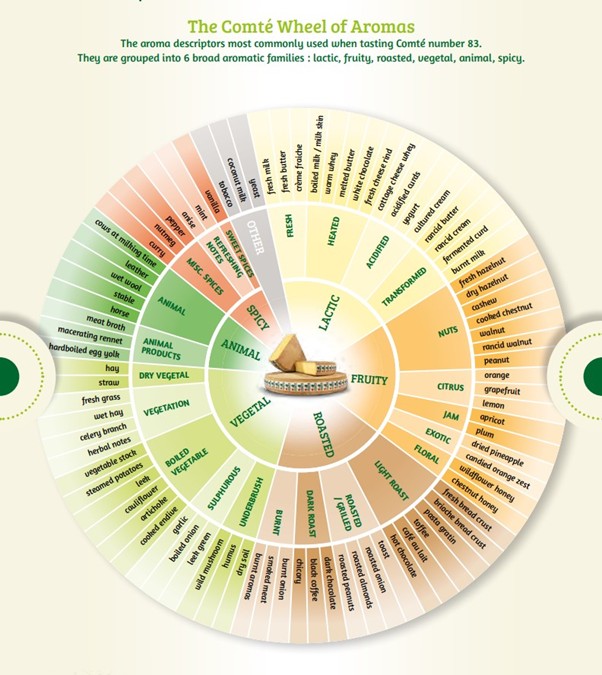

We tasted wheels from different ages: 12-month, 18-month, 24-month. The longer

aged ones showed off deeper savoury notes, hints of caramelised onion, hay, and

citrus. It’s the kind of cheese that rewards time and careful work — but that approach

is becoming harder to defend in the current industry landscape.

The Comté Controversy: Tradition Meets Environmental Pressure

Comté has AOP (Appellation d’Origine Protégée) status, that meant to ensure quality

and protect traditional production. But in recent years, concerns have been growing

among producers and affineurs about the sustainability and integrity of what gets

labelled as Comté. The biggest issue isn’t flavour, it’s environmental sustainability. Environmenta

activist and animal-rights campaigner Pierre Rigaux, founder of Nos Viventia, called

for a boycott of Comté cheese, arguing that its skyrocketing production is harmful to

the environment and cruel to cows. Many of the newer, larger producers still operating under the AOP are relying more heavily on silage based feed and lowland farming, often with year-round milk

production. These systems allow for higher yields, but they diverge from traditional,

seasonal, pasture-based dairy farming. That shift has major consequences:

- Biodiversity Loss: traditional mountain pastures, where cows graze on diverse

flora, are being replaced or neglected. That botanical diversity directly affects

the complexity of the milk and therefore the cheese. But it also supports

ecosystems and pollinators that are disappearing elsewhere in Europe. - Carbon Footprint: silage-heavy and intensive dairy systems rely more on

imported feed, machinery, and fertilisers. In contrast, pasture-based systems

in the Jura are largely self-sustaining, requiring less external input and

producing lower emissions per litre of milk. - Water Stress: climate change is already putting pressure on water availability

in the region. Some newer systems need more water, not just for the animals

but also for growing feed. The traditional model of cows grazing outdoors,

eating hay in winter is far more efficient. Intensive dairy farming in the Jura

region has led to elevated nitrogen and phosphorus runoff, causing algal

blooms and alarming fish die-offs in rivers like the Loue.

While Comté is deeply cherished as part of France’s culinary identity, its booming

production raises legitimate environmental and welfare concerns. The debate is

pushing stakeholders, like Marcel Petit to find ways to ensure Comté remains both

sustainable and emblematic of French tradition.

We spoke to a representative from Marcel Petite, who gave us the tour around the

fort, and we asked about the controversies listed above. He ensured us that Marcel

Petit works only with milk from farms committed to those traditional methods: no

silage, seasonal calving, grass and hay diets, and smaller-scale production. For

example, they only work with 33 out of 150 farmers who make Comté. They believe,

and I agree, that this isn’t just about taste, it’s about protecting a viable food system

in the long term.

Strict rules for Comté production

- Area of production: Doubs, Jura, Ain (at an elevation of 1500-4500 ft)

- Milk must come from Montbéliarde (95%) and Simmental (5%) breeds, of which that are approximately 112,000 cows.They must each have access to 2.5 acres of natural pasture.

- The feed must be natural and free of fermented products and GMOs.

- Every ‘fruitière’ must collect milk from dairy farms within a 17-mile diameter

- maximum.

- Milk must be turned be turned into cheese within a maximum of 24 hours othe cows being milked.

- Only natural ferments must be used to turn milk into curds.

- Comté must be aged on spruce boards, at a minimum of 4 months, but usually 6-18 months, and sometimes double this.

Why It Matters in London

Back in London, I often get asked why some Comté is cheaper than others. The

answer, increasingly, is about more than just maturity or branding. When you buy Comté matured by Marcel Petite, you’re supporting a supply chain that’s lower-impact, biodiversity-friendly, and rooted in mountain farming. The flavour is more complex, but it also reflects a commitment to sustainability.

As the cheese world wrestles with questions of scale, climate, and authenticity, Comté is at the forefront of this. Can we keep traditional methods alive while feeding modern demand? Or will volume and efficiency prevail? So far, the fight isn’t settled. But for those of us on the retail side, it’s our job to tell

the story behind the rind, and make sure people know what they’re really tasting.

What to Look for When Buying Comté

- Age: Ask for the date when the Comté was produced, not what month stamp it

has on it. Affineur: ask where it was aged, names like Marcel Petite, Rivoire-Jacquemin,

or Vagne often signal quality. - Affineur: Milk Source: cheeses made from grass-fed, mountain-farmed milk tend to

have more interesting, nuanced flavour, and a lower environmental footprint. - Texture and Taste: properly aged Comté should be firm but not dry, with nutty,

buttery notes and a long finish.

Final Thought:

In a time when food choices are increasingly political and ecological, Comté is more than just an old mountain cheese. It’s a case study in what happens when heritage meets modern pressure and a reminder that good cheese should do more than taste good. It should make sense for the land, the animals, and the people who make it.

By William Booth-Farmer